At the end of his Aug. 17-21 China visit, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad announced that US$22 billion of Chinese-backed infrastructure projects in his country would be temporarily or permanently cancelled. The world will be watching China’s subsequent actions to see whether they will take on a neocolonialist tint.

The Belt and Road Initiative is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s grandiose plan to connect China with South, Central and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Russia, Africa, Latin America and Europe through infrastructure projects including roads, ports, airports and railways.

The broad geographic reach of the BRI, as it has come to be known, has raised questions whether China intends to use this project for imperial expansion. As Asia Sentinel has previously reported, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Pakistan have found themselves so deep in debt to the Chinese that there are fears political domination will follow. The risk is that Malaysia is on the same course.

The postponed Malaysian projects include an East Coast Rail Link and two energy pipelines. Mahathir said told a Beijing press conference on Aug. 21 that the three would be “deferred until such time we can afford, and maybe we can reduce the cost also if we do it differently. It’s all about borrowing too much money which we can’t afford, can’t repay, and also we don’t need those projects for Malaysia at this moment.”

The vast majority of the funding for three — US$20 billion for the rail link and US$2 billion for the pipelines – has been supplied by the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank), a state-owned policy lender. Chinese state-owned firms are the main contractors of these three projects, raising criticism that Malaysians are being denied jobs, as they have been in several countries where the belt and the road have reached.

At a press conference of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the same day, when asked about the cancellation of these projects, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman said, “Of course, cooperation between any two countries may encounter some problems, and different views may emerge at different times. These problems should be properly resolved through friendly consultations without losing sight of the friendship enjoyed by the two countries and the long-term development of bilateral ties, which, I can assure you, is also an important consensus reached during Prime Minister Mahathir’s visit to China.”

Mahathir was tactful enough not to criticize China for these stalled projects, but to lay the blame on his predecessor Najib Razak, who had approved them projects while he was Malaysia’s premier. After being ousted in a shock defeat in the Malaysian elections on May 9, Najib is facing corruption charges over the hugely mismanaged and corrupt 1Malaysia Development Bhd, backed by the Ministry of Finance.

However, Mahathir warned China against being a neocolonialist. At a press conference in Beijing with Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang on Aug. 20, when asked by Li whether he supported free trade, Mahathir replied, “I agree free trade is the way to go, but, of course, free trade should also be fair trade. We do not want a situation where there is a new version of colonialism happening because poor countries are unable to compete with rich countries, therefore we need fair trade.”

Ironically, Chinese state propaganda expresses similar opposition to colonialism, in its messages conveyed in two Beijing museums, the National Museum and the China Railway Museum. As stated part of the reason for the Republican Revolution of 1911 was the Chinese people’s opposition to foreign domination of China’s railroads. By 1911, foreign powers, including Russia, Japan, Germany, Britain and France, controlled 93 percent of China’s railways, a display in the National Museum pointed out. The Qing government had to pay off huge debts to foreign banks which had bankrolled these railroads.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the Qing government nationalized railways owned by private Chinese businesses, then sold them to foreign interests. This sparked a rebellion, causing the Chinese imperial government to transfer troops from the Chinese city of Wuhan to quell a rail revolt in Sichuan province. As a result, the Wuhan garrison was undermanned, which enabled an uprising in Wuhan to succeed in October 1911, which in turn toppled the Qing dynasty.

Going forward, the Chinese government must avoid provoking resistance to Chinese-funded infrastructure projects in BRI countries whose governments and peoples fear dependency, just as China was reduced to a semi-colonial state by foreign dominance of its infrastructure. Currently, BRI projects are mostly financed by Chinese state-owned banks, just as foreign banks funded most of the railway in China during the Qing dynasty.

At the Aug. 20 press conference, Mahathir expressed his wish that Beijing will be sympathetic to Malaysia’s heavy debt and help resolve its fiscal problems. At the press conference on August 21, the 93-year old leader said, “I believe China itself does not want to see Malaysia become a bankrupt country.”

The Chinese government has a vested interest in ensuring Malaysia’s economy is not sunk by crushing debt if Beijing and Chinese state-owned firms wish to avoid a repeat of the derailment of a US$7.5 billion rail project in Venezuela.

On Apr. 11, 2013, the South China Morning Post reported that this 475 km railway, built by the state-owned China Railway Group, was delayed because the Venezuelan government was unable to pay the entire US$7.5 billion contract. The Venezuelan government owed China Railway US$400 million to US$500 million, Li Changjin, the chairman of China Railway, was quoted as saying. “The reason is the Venezuelan government has no money.”

Onsite media reports in 2016 showed China Railway’s facilities in its Venezuela project were apparently abandoned.

Since 2013, Venezuela’s economy has been in a dire state, with high inflation and difficulty repaying its debts. If Beijing wants the BRI to succeed in countries like Venezuela and Malaysia, it must ensure that costly infrastructure projects do not harm these countries’ economies. Otherwise, trade and investment between them and China will suffer.

During their Aug. 20 meeting, Xi told Mahathir their nations should have pragmatic cooperation, seeking innovative new models of cooperation. Xi must find viable models of cooperation over BRI if he wishes to avoid blowback against Chinese projects in Malaysia. Only then can Xi demonstrate that Belt and Road is not a Trojan Horse for Chinese imperialism, and convince nations to accept the vast infrastructure projects.

Toh Han Shih is a Singaporean writer in Hong Kong

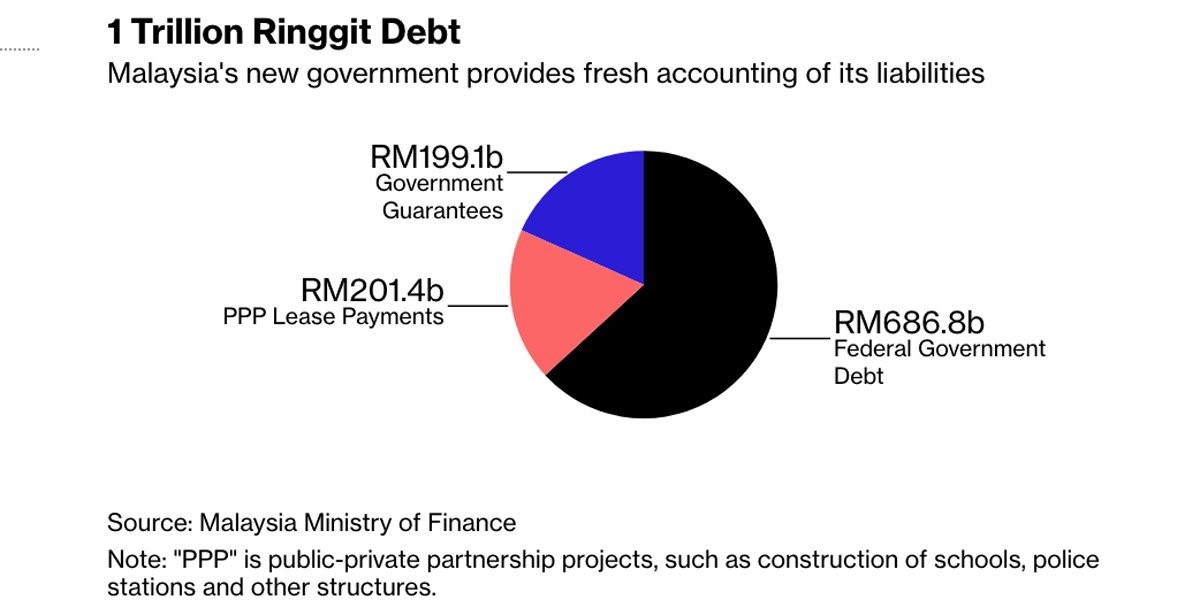

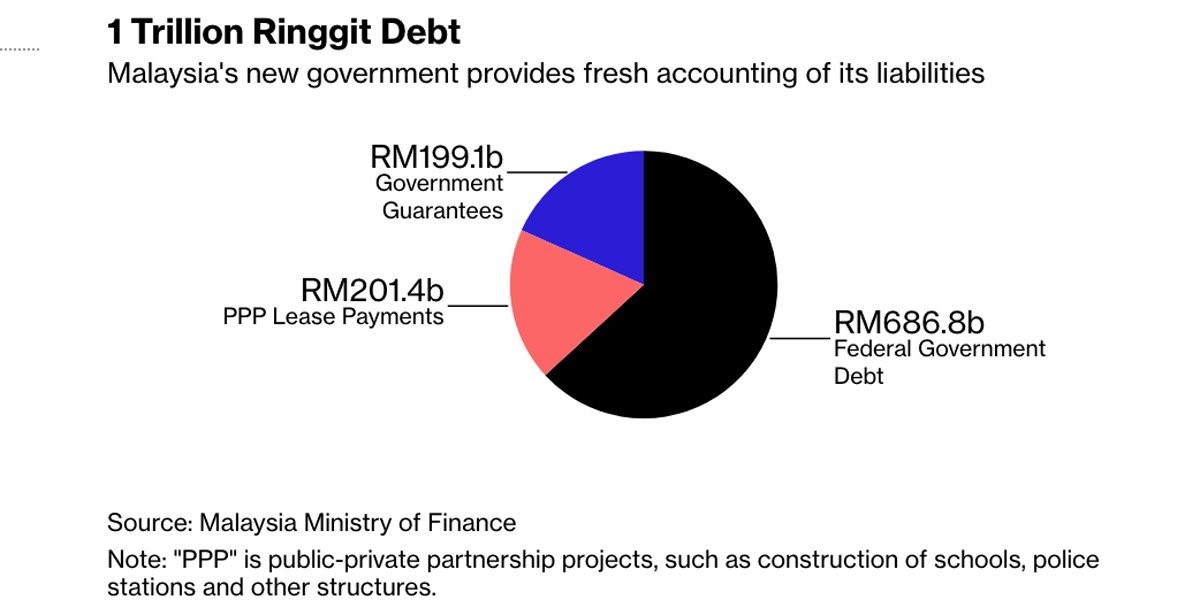

We wish to say “I told you so” again. But to hear it from the horse mouth – Mahathir – is equally satisfying. Yes, Malaysia has already breached the RM1 trillion marks, for the wrong reason. Speaking for the first time to staff of the prime minister’s office, Mahathir revealed the troubling debts accumulated, thanks to 9 years of corrupt Najib administration.

When Mahathir resigned in 2003 after ruling for 22 years (1981 to 2003), the debt was only about RM190 billion. After he passed the baton to Abdullah Badawi, the sleeping head doubled the nation’s debt to about RM380 billion. But after Najib Razak took over the country, he tripled it to RM1 trillion in debts. In short, Najib doubled the debt in 4 years what Badawi would have done in 8 years.

During the 14th election campaign, Najib Razak conveniently used the national debt as a weapon to attack his opposition. He warned the people that a victory for the opponent coalition Pakatan Harapan’s would cause debt to skyrocket. He claimed that the opposition’s promise to abolish GST (goods and services tax) and road toll collection would increase national debt to RM1.1 trillion.

Najib, of course, didn’t want the people to know that his regime had already clocked the RM1 trillion figures. By first quarter of 2017, the country was already burdened with RM916.12 billion. Since Najib came to office in 2009, Malaysia’s debt has grown at an average of 10% a year. Hence, if you look at the government gross debt chart, the first number of debt figure will jump – every year (get the picture?).

Najib, of course, didn’t want the people to know that his regime had already clocked the RM1 trillion figures. By first quarter of 2017, the country was already burdened with RM916.12 billion. Since Najib came to office in 2009, Malaysia’s debt has grown at an average of 10% a year. Hence, if you look at the government gross debt chart, the first number of debt figure will jump – every year (get the picture?).

The worst part is this – despite abolishing subsidies for petrol, diesel, sugar, cooking oil, electricity tariffs, water and whatnot, Najib regime somehow still couldn’t find the money to run the government efficiently. The son of Razak was practically stealing rice from a beggar’s bowl when he introduced 6% GST (goods and services tax) on 1 April 2015.

Do you need more proof that the despicable and corrupt Najib had been stealing from the people to live lavishly? The clearest proof of excessive spending, and even corruption for that matter, can be found in this chart – the yearly allocation for the Prime Minister Office (PMO). In his first year as prime minister, the budget for the PMO breached RM10 billion for the first time in the history.

The yearly budget for the PMO continued to climb and reached the climax when it hit the RM20 billion in 2016. Now we know why a small nation with 32-million populations need to pay RM20 billion for the operation of Najib’s office. After the stunning defeat of Barisan Nasional coalition government, it is discovered that a whopping 17,000 “political appointees” were hired by the previous government.

Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, shocked, said the contracts for the highly paid 17,000 “political appointees” will be axed. This will reduce the expenditure. Assuming each of them was paid a conservative RM5,000 every month, the annual expenses would hit RM1 billion already. When Mahathir resigned in 2003, the PMO was allocated merely RM3.5 billion.

However, paying top dollar for 17,000 “political appointees” to boost Najib’s image wasn’t the only wastage policy adopted by the former prime minister. His wife, Rosmah Mansor, was the biggest beneficiary from the massive yearly budget to the PMO. Auntie Rosie’s pet project – Permata Programme – was allocated RM100 million and RM111 million in 2010 and 2011 Budget respectively.

When Najib presented the 2013 Budget, the so-called pre-school education programme was allocated a whopping RM1.2 billion. The amazing part about the “Permata” programme is that nobody knows how the money was being used. In fact, the programme has been such a cash-cow to Rosmah that even after his husband has lost, she insisted the new government to retain the project.

Najib’s previous government operated without transparency. As the finance minister himself, he spent excessively and lavishly without thinking about the source of income. His answer to lack of funding was to borrow money. One of Najib’s tricks in hiding the RM1 trillion debts accumulated over the years – exclude the government-guaranteed debt.

Based on statistic from Bank Negara Malaysia (Central Bank), the debt guaranteed by the Federal Government is at eye-popping RM238 billion. And thanks to the declassification of 1MDB audit report after Najib was defeated in the 14th general election, it has been revealed that the state investment fund was drowning in debt. Now, where is that Arul “Anaconda” Kanda guy when you need him the most?

According to the audit report – assuming there are no new loans after October 2015 – it was estimated that RM42.26 billion was needed to pay the principal and interest that will be due between November 2015 and May 2039. 1MDB also needs a minimum of RM1.52 billion every year for 10 years from November 2015 to May 2024 just to pay back its loans.

In short, the declassified report said the scandal-tainted firm had debt commitments totalling RM74.6 billion, inclusive of interest and borrowing costs, from November 2015 to 2039. That’s about RM3 billion of debt commitment every year – for the next 25 years. This is what going to make the country in serious trouble, if billions of dollars plundered by Najib is not recovered.

Now, do you understand why newly sworn-in finance minister Lim Guan Eng is roped in to clean the shit left by the former Thief-in-Chief Najib Razak? Based on his track record in managing Penang finances, only Mr. Lim has the ability to fix the problem. Crooked Najib was essentially driving the country to the brink of bankruptcy, had he not stopped in time.

Copyright 2006-2018. FinanceTwitter. All rights reserved

Had Najib Razak won the 14th general election on May 9th, his first foreign visit will most likely be China. He would go there and brag how his Barisan Nasional coalition government had used President Xi Jinping photo on campaign billboard. He would offer Xi to restart the stalled “Bandar Malaysia” project in exchange for kickbacks, and sell more national treasure to China.

Yes, as revealed by the new government, the Najib regime had “secretly” used taxpayers’ money to bail out 1MDB since April 2017 to the tune of RM6.98 billion, and counting. And he would certainly continue to sell more strategic assets to China. The revelation that Malaysia has breached the RM1 trillion in debts confirms the country was on the brink of bankruptcy.

Judging by how the defiant Najib continues to twist and deny about the RM1 trillion debt and 1MDB bailout, it’s safe to presume the mad son of Razak would most likely continue to borrow and hide the debts using creative accounting – had he won on May 9th. Unfortunately to the ex-prime minister, his lucky number didn’t work and his wife’s black magic had failed spectacularly.

While the new government is trying to fix the financial havoc left by the previous government, where the ex-PM Najib helped himself to the national coffers as if they were his personal piggie bank, there’s one problem that has gotten Mahathir cracking his 93-year-old head – China. Between the corrupted Najib and the no-nonsense Mahathir, the choice isn’t hard for Beijing.

As China aggressively grows its influence in its backyard and worldwide, a greedy and corrupt scumbag like Najib is what the Middle Kingdom desires. Najib can be controlled and become China’s puppet. But with Mahathir, a man who doesn’t fancy women, let alone hungry for money, Beijing will be having problem transforming Malaysia as its obedient puppet against the United States in the region.

However, at the same time, Mahathir – world’s oldest prime minister – cannot afford to offend China. What the world’s second largest economic powerhouse needs to do to give a hard time to the newly installed prime minister is to stop importing palm oil from Malaysia. When the palm oil prices plunge, the Felda settlers, mostly ethnic-Malay, would be sharpening their knives for Mahathir’s head.

That was why Malaysia’s richest man – Robert Kuok – was invited to be one of five members of a special advisory council, which Mahathir called the “council of the elders”. Kuok was chosen because of his special relationship with Beijing, including President Xi Jinping. It is hoped that Kuok could facilitate projects re-negotiation between Kuala Lumpur-Beijing.

Still, like other countries being trapped in the so-called China’s OBOR (One Belt One Road) flagship project, Malaysia owes huge debts thanks to Najib Razak. Based on data compiled by “This Week in Asia” from 11 high-profiles, controversial projects signed during the Najib administration was in the region of US$134 billion worth of Chinese investment.

Those projects, involving 13 Chinese companies and financial institutions, range from real estate development to infrastructure construction and large-scale industrial plants. Most of them were signed in the last 5 years and remain under construction. One of them includes the ongoing East Coast Railway Link (ECRL), a wasteful project where the cost has been inflated to RM55 billion.

About 85% of the ECRL railway project is financed by Chinese soft loans from China Exim Bank. Mahathir has clarified that while he’s not anti-China, his administration is indeed against the huge borrowing. Sure, Mahathir can, with helps from Robert Kuok, renegotiate the terms of projects such as ECRL. But it is unlikely to be terminated. China won’t allow it to happen, for obvious reason.

Costing RM55 billion at its initial first phase, the ECRL is expected to cost taxpayers RM92 billion by the time it paid off its due interest. The second phase would cost another RM11 billion. The contract for the ECRL was obviously “strange” – the terms state that the contractor must be from China while the borrowings of RM55 billion to fund the project must also come from the country.

Enter Japan – Mahathir Mohamad’s first foreign destination. Scheduled to take place on June 11-12, the Malaysian 7th prime minister will attend the annual Nikkei Conference and is expected to rub shoulders with Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, whom called Mahathir on May 24 to specifically congratulate him on the formation of the new government.

The relationship between Mahathir and Japan went as far back as 1981 when the Malaysian premier promoted “Look East” policy. The policy was mooted to encourage Malaysian students in Japan to bring back knowledge and acquire Japanese cultural virtues such as work ethics, discipline and punctuality – in addition for Japan’s assistance in Malaysia’s development.

This time, Mahathir, making a comeback after ruled for 22 years (1981 to 2003), is expected to request for assistance not only to reduce the huge borrowings but also to seek investments to boost Malaysia’s economy and to instil investors’ confidence. And Japan will gladly help in whatever way possible as the Japanese is fast losing its shine among Southeast Asian countries.

Tokyo has suffered a series of foreign policy setbacks in the region as an increasing number of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) members began gravitating toward China’s enormous and fast growing economy. Besides former Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Mahathir is the only leader who had refused to “kow-tow” to powerful nation such as China.

More importantly, Mahathir’s revisit of his “Look East” policy is a strategic move to send a message to China – that Malaysia has other wealthy friends such as Japan. And guess which country that China hates the most in the region. Yes, it’s none other than the Japanese. Most of ASEAN countries have been charmed by China’s deep pocket.

Despite his advanced age, Mahathir’s aura cannot and should not be underestimated. After all, not a single foreign country had predicted the stunning victory of the old man. Therefore, Mahathir’s visit and comments in Japan will be closely watched and scrutinized. He could share his critical view about China’s naval expansion in the South China Sea.

Mahathir could probably use the platform in Japan to tell China that unlike the disgraced Najib Razak, he is not ready to bend over in exchange for kickbacks. That Mahathir cannot be bribed and refused to be controlled will make China more than willing to re-negotiate the present lopsided projects not favourable to the Malaysian people.

In the same breath, PM Mahathir might drop the Singapore-Kuala Lumpur high-speed rail (HSR) project, although the 350-km rail deal between Singapore and Malaysia had been inked in 2016 under the previous PM Najib Razak. Already, the new Malaysian government is studying how much they need to pay in the event the RM100 billion “wasteful and unnecessary” HSR project is scrapped entirely.

However, one cannot underestimate whether this is one of Mahathir’s negotiation tactics to force Singapore and China to submit to his demands. Mahathir may threaten to drag Singapore to international court to arbitrate if the terms of the HSR project are too heavily weighted in one party’s favour, which in this case is Singapore, of course.

Despite scoring high marks on Corruption Perceptions Index, Singapore isn’t as clean as many think. It wasn’t until the F.B.I opened investigation papers and Switzerland dropped the bombshell that a criminal investigation into 1MDB had revealed that about US$4 billion appeared to have been misappropriated from Malaysian state companies, that Singapore was forced to act in early 2016.

Therefore, Mahathir could use HSR project to paint Singapore as a crook working together with Najib. One way or another, Singapore had aided Najib steal and stash billions in the island. That was why an hour after Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong left Mahathir’s office, embarrassingly, it was announced that all bilateral deals signed by ex-PM Najib Razak has to be re-looked at.

Even if Mahathir cannot cancel the HSR project, bringing Japan to the table could send shivers down China’s spine. With over US$134 billion worth of investment, China will do anything to secure their investment and influence in the country. And the Chinese definitely do not want Malaysia to side with Singapore, let alone Japan, in any dispute with them.

Beijing considers Singapore as a proxy of the U.S., hence both countries doesn’t see eye to eye. Likewise, Singapore doesn’t want to see China hardware in their backyard. It becomes merrier when the Japanese are thrown into the party, either as new banker or new player. Mahathir will definitely squeeze something juicy from his visit to Japan.

Had Najib Razak won the 14th general election on May 9th, his first foreign visit will most likely be China. He would go there and brag how his Barisan Nasional coalition government had used President Xi Jinping photo on campaign billboard. He would offer Xi to restart the stalled “Bandar Malaysia” project in exchange for kickbacks, and sell more national treasure to China.

Yes, as revealed by the new government, the Najib regime had “secretly” used taxpayers’ money to bail out 1MDB since April 2017 to the tune of RM6.98 billion, and counting. And he would certainly continue to sell more strategic assets to China. The revelation that Malaysia has breached the RM1 trillion in debts confirms the country was on the brink of bankruptcy.

Judging by how the defiant Najib continues to twist and deny about the RM1 trillion debt and 1MDB bailout, it’s safe to presume the mad son of Razak would most likely continue to borrow and hide the debts using creative accounting – had he won on May 9th. Unfortunately to the ex-prime minister, his lucky number didn’t work and his wife’s black magic had failed spectacularly.

While the new government is trying to fix the financial havoc left by the previous government, where the ex-PM Najib helped himself to the national coffers as if they were his personal piggie bank, there’s one problem that has gotten Mahathir cracking his 93-year-old head – China. Between the corrupted Najib and the no-nonsense Mahathir, the choice isn’t hard for Beijing.

As China aggressively grows its influence in its backyard and worldwide, a greedy and corrupt scumbag like Najib is what the Middle Kingdom desires. Najib can be controlled and become China’s puppet. But with Mahathir, a man who doesn’t fancy women, let alone hungry for money, Beijing will be having problem transforming Malaysia as its obedient puppet against the United States in the region.

However, at the same time, Mahathir – world’s oldest prime minister – cannot afford to offend China. What the world’s second largest economic powerhouse needs to do to give a hard time to the newly installed prime minister is to stop importing palm oil from Malaysia. When the palm oil prices plunge, the Felda settlers, mostly ethnic-Malay, would be sharpening their knives for Mahathir’s head.

That was why Malaysia’s richest man – Robert Kuok – was invited to be one of five members of a special advisory council, which Mahathir called the “council of the elders”. Kuok was chosen because of his special relationship with Beijing, including President Xi Jinping. It is hoped that Kuok could facilitate projects re-negotiation between Kuala Lumpur-Beijing.

Still, like other countries being trapped in the so-called China’s OBOR (One Belt One Road) flagship project, Malaysia owes huge debts thanks to Najib Razak. Based on data compiled by “This Week in Asia” from 11 high-profiles, controversial projects signed during the Najib administration was in the region of US$134 billion worth of Chinese investment.

Those projects, involving 13 Chinese companies and financial institutions, range from real estate development to infrastructure construction and large-scale industrial plants. Most of them were signed in the last 5 years and remain under construction. One of them includes the ongoing East Coast Railway Link (ECRL), a wasteful project where the cost has been inflated to RM55 billion.

About 85% of the ECRL railway project is financed by Chinese soft loans from China Exim Bank. Mahathir has clarified that while he’s not anti-China, his administration is indeed against the huge borrowing. Sure, Mahathir can, with helps from Robert Kuok, renegotiate the terms of projects such as ECRL. But it is unlikely to be terminated. China won’t allow it to happen, for obvious reason.

Costing RM55 billion at its initial first phase, the ECRL is expected to cost taxpayers RM92 billion by the time it paid off its due interest. The second phase would cost another RM11 billion. The contract for the ECRL was obviously “strange” – the terms state that the contractor must be from China while the borrowings of RM55 billion to fund the project must also come from the country.

Enter Japan – Mahathir Mohamad’s first foreign destination. Scheduled to take place on June 11-12, the Malaysian 7th prime minister will attend the annual Nikkei Conference and is expected to rub shoulders with Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, whom called Mahathir on May 24 to specifically congratulate him on the formation of the new government.

The relationship between Mahathir and Japan went as far back as 1981 when the Malaysian premier promoted “Look East” policy. The policy was mooted to encourage Malaysian students in Japan to bring back knowledge and acquire Japanese cultural virtues such as work ethics, discipline and punctuality – in addition for Japan’s assistance in Malaysia’s development.

This time, Mahathir, making a comeback after ruled for 22 years (1981 to 2003), is expected to request for assistance not only to reduce the huge borrowings but also to seek investments to boost Malaysia’s economy and to instil investors’ confidence. And Japan will gladly help in whatever way possible as the Japanese is fast losing its shine among Southeast Asian countries.

Tokyo has suffered a series of foreign policy setbacks in the region as an increasing number of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) members began gravitating toward China’s enormous and fast growing economy. Besides former Singapore Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Mahathir is the only leader who had refused to “kow-tow” to powerful nation such as China.

More importantly, Mahathir’s revisit of his “Look East” policy is a strategic move to send a message to China – that Malaysia has other wealthy friends such as Japan. And guess which country that China hates the most in the region. Yes, it’s none other than the Japanese. Most of ASEAN countries have been charmed by China’s deep pocket.

Despite his advanced age, Mahathir’s aura cannot and should not be underestimated. After all, not a single foreign country had predicted the stunning victory of the old man. Therefore, Mahathir’s visit and comments in Japan will be closely watched and scrutinized. He could share his critical view about China’s naval expansion in the South China Sea.

Mahathir could probably use the platform in Japan to tell China that unlike the disgraced Najib Razak, he is not ready to bend over in exchange for kickbacks. That Mahathir cannot be bribed and refused to be controlled will make China more than willing to re-negotiate the present lopsided projects not favourable to the Malaysian people.

In the same breath, PM Mahathir might drop the Singapore-Kuala Lumpur high-speed rail (HSR) project, although the 350-km rail deal between Singapore and Malaysia had been inked in 2016 under the previous PM Najib Razak. Already, the new Malaysian government is studying how much they need to pay in the event the RM100 billion “wasteful and unnecessary” HSR project is scrapped entirely.

However, one cannot underestimate whether this is one of Mahathir’s negotiation tactics to force Singapore and China to submit to his demands. Mahathir may threaten to drag Singapore to international court to arbitrate if the terms of the HSR project are too heavily weighted in one party’s favour, which in this case is Singapore, of course.

Despite scoring high marks on Corruption Perceptions Index, Singapore isn’t as clean as many think. It wasn’t until the F.B.I opened investigation papers and Switzerland dropped the bombshell that a criminal investigation into 1MDB had revealed that about US$4 billion appeared to have been misappropriated from Malaysian state companies, that Singapore was forced to act in early 2016.

Therefore, Mahathir could use HSR project to paint Singapore as a crook working together with Najib. One way or another, Singapore had aided Najib steal and stash billions in the island. That was why an hour after Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong left Mahathir’s office, embarrassingly, it was announced that all bilateral deals signed by ex-PM Najib Razak has to be re-looked at.

Even if Mahathir cannot cancel the HSR project, bringing Japan to the table could send shivers down China’s spine. With over US$134 billion worth of investment, China will do anything to secure their investment and influence in the country. And the Chinese definitely do not want Malaysia to side with Singapore, let alone Japan, in any dispute with them.

Beijing considers Singapore as a proxy of the U.S., hence both countries doesn’t see eye to eye. Likewise, Singapore doesn’t want to see China hardware in their backyard. It becomes merrier when the Japanese are thrown into the party, either as new banker or new player. Mahathir will definitely squeeze something juicy from his visit to Japan.

Copyright 2006-2018. FinanceTwitter. All rights reserved

Global Times, often considered as the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, has unleashed its first warning shot at the new government of Malaysia. After 93-year-old Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad ditched a planned HSR (high-speed rail) between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, the Chinese media seemed very upset.

The mouthpiece cried, whined and bitched that all the efforts have gone down the drain after Mahathir denied companies from China, Japan, South Korea, Europe, Singapore and Malaysia the opportunity to bid for the RM110 billion project. Global Times also questioned if this is the way the new government of Mahathir keeps its promises over contract.

What type of grass has Global Times been smoking? Perhaps the media can’t differentiate between a communist and a democracy country, for obvious reason. Mahathir is the new prime minister of a new Pakatan Harapan coalition government, NOT the old corrupted Barisan Nasional coalition government. That old regime led by Najib Razak had collapsed.

Therefore, it’s quite an idiotic statement to say Mahathir government has broken his promise. How could Mahathir promise to keep the HSR project when abolishing the high-speed rail has been Pakatan Harapan’s manifesto from the beginning? And how does China know that they will definitely win the project, unless of course, Global Times knew that Beijing had already bribed Najib.

The Chinese media insisted that Malaysia must pay compensation if the new government wants to review the HSR or ECRL projects. It also write – “The Chinese government will also take concrete measures to safeguard the interests and rights of Chinese enterprises.” Did Global Times just threatened to send its mighty military forces to invade Malaysia if the country refuses to pay?

Hmm, perhaps Mahathir should pretend to be panicked and invite the U.S. to setup a military base in Sabah so that U.S. Navy destroyers and aircraft carrier could sail near to China’s man-made islands in Spratly Islands whenever those American sailors have nothing better to do. The Global Times reporter might be clueless that Sabah and Sarawak are part of Malaysia.

The best part of the article, written by Hu Weijia, was when it said – “Chinese-funded projects are not a gift that Kuala Lumpur can refuse without compensation.” Seriously? A gift? Well, nobody in their right mind would refuse a 350-km HSR (RM110 billion) and a 688-km ECRL (RM55 billion) project if they were indeed free gifts from China. Unfortunately, they are not.

The ECRL (East Coast Rail Link) was inflated from an initial RM30 billion to RM55 billion. And that’s just the first phase. The second phase would cost another RM11 billion. By the time the whole project is fully paid off, the white elephant would cost an eye-popping RM92 billion. And it was Beijing who was working hand-in-glove with crook Najib to plunder the country’s national coffers.

The contract for the ECRL was obviously “strange” – the terms state that the contractor must be from China while the borrowings of RM55 billion to fund the project must also come from the country. In fact, the loan for the project is kept abroad, suggesting that the inflated cost was used to pay 1MDB debts and to pay kickbacks to Najib Razak. That is one heck of a hanky-panky deal.

Heck, the contract also included unusual practice such as that payments to China Communications Construction Co Ltd (CCCC) from Export-Import Bank of China are based on a predetermined timetable, and not on the basis of work done. This means even if the Chinese CCCC didn’t do any work at all, they would be paid because the schedule payment says so.

In essence, the RM55 billion loans from China never reached Malaysia banking system. The Chinese bank will pay a Chinese contractor in China. And Malaysia taxpayers would be slapped with the bill for the mega-project. So, which part of the terms looks or smells like a gift to Global Times? Perhaps Hu Xijin, the editor-in-chief of Global Times, should relook at the half-past-six article.

Amusingly, the article also said – “It’s very easy for Chinese companies to shift their focus to other countries, but Malaysia’s economy is the one that will suffer big losses.” Sure, go ahead and take your money elsewhere. Why do you think Mahathir’s first foreign trip is to Japan, and not China? But hey, relax. Global Times doesn’t necessary represent President Xi Jinping’s final policy.

The mouthpiece is just one of many poodles of Beijing. The media was unleashed specifically to test water – to threaten and scare the shit out of PM Mahathir and see if the old man would chicken out. The same media had bashed Mahathir before he became the world’s oldest prime minister, when he criticised the RM170 billion Forest City as a threat to national sovereignty.

Get real, China will not invade Malaysia over cancellation of HSR or renegotiation of ECRL project. Chinese Ambassador to Malaysia, Bai Tian, has announced that 3 Chinese enterprises have invested RM1.2 billion in Malaysia in the first week following the formation of the new government. They would not burn the bridge after 44 years of mutually-benefiting cooperation between both nations.

The ECRL project was not really about business decision. It was about geo-political needs for China. It just happen that the scumbag Najib was so corrupted that he was willing to sell anything to China, hence Beijing played along. The success of ECRL is of paramount important to China largely because about 80% of the world’s maritime trade between east and west passes through the Straits of Malacca.

The project will connect ports on the east and west coasts of Peninsular Malaysia and will essentially alter the present regional trade routes, which ply between the busy Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea via Singapore. However, Singapore, sitting in a strategic position along the east-west route, is no friend of China but a proxy of rival United States.

The ECRL acts as a land bridge between Port Klang and Kuantan Port, and will enable China-bound goods from Port Klang, inland and the north to be moved to Kuantan Port, without having to go south to Singapore. In fact, the state is reclaiming land along the Straits of Malacca to build a port to offer oil storage, repair and refuelling services for huge tankers.

More importantly, there’s one secret reason why China desperately needs ECRL project to be successful. Thanks to Americans’ consistent intimidation in the South China Sea, China realized that a simple blockade of the Strait of Malacca by the U.S. and its alliance will cut China off from Middle East oil supplies and from its “Second Continent” Africa.

Just like China’s first permanent overseas military in Djibouti, China needs Port Klang and Kuantan Port to serve as its logistics centre for whatever purpose. Therefore, it’s bullshit when Global Times said China is more than happy to shift its focus to other countries. China needs ECRL as much as Mahathir needs to re-negotiate the “very damaging” terms signed by Najib Razak.

Mahathir knew how important ECRL project is to China from the geo-political perspective. He also knew government to government contracts usually had a mechanism to resolve dispute such as the current one. Besides, Mahathir can always refer the matter to international arbitration because such contract will usually have a clause to allow one party to do so.

The question is this – is China willing to re-negotiate terms of contract or risk having the project terminated early with Malaysia willing to pay the compensation? China has to decide if money is more important than its OBOR (One Belt One Road) initiative in the region. Mahathir can always get soft-loan from Japan to help lift the burden of debts.

Copyright 2006-2018. FinanceTwitter. All rights reserved

On May 15, just five days after the inauguration of Mahathir Mohamad as the world’s oldest prime minister, Daim Zainuddin fired a warning shot. He said it would be foolish for Anwar Ibrahim to be made prime minister immediately upon returning to parliament. The warning shot was aimed at Anwar, and not his boys, as Daim would like the public to believe.

Coming from the head of Mahathir’s influential “Council of Elders”, such statement was actually very disturbing. It simply means Anwar was absolutely impatient to be crowned as the next prime minister, so much so that he was prepared to break the agreement among the four component parties making up the Pakatan Harapan coalition.

Interestingly, Anwar revealed how the ousted former premier Najib Razak was “totally shattered” the night he lost the general election and called his jailed rival – Anwar Ibrahim – twice for advice on what he should do. Anwar claimed – “When he called on the night of the election, I advised him as a friend to concede and move on.”

Was Anwar the secret lover of Najib? Was Anwar the long lost biological brother of Najib? If not, does it make any sense that of all the people in the world, ex-PM Najib had chosen to call his enemy seeking advice or looking for a shoulder to cry on? You don’t need a rocket scientist to tell that Mr. Najib had called Mr. Anwar and offered him a deal to jump ship.

Mr. Anwar actually didn’t have to divulge the secret calls he received from the despicable Najib Razak. Nobody would know about the calls anyway. Since the revelation, Najib had neither acknowledged nor denied making such calls. So, those calls on May 9th must be genuine. But why did Anwar reveal the calls? Was he trying to brag about it?

There are two possibilities. First, PM-in-waiting Anwar Ibrahim wanted to send a message to Mahathir Mohamad that his PKR (People’s Justice Party) could jump ship and form the federal government with Najib’s Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition. Second, Anwar was worried that the secret calls could eventually leak hence it would be smarter to disclose it beforehand.

So, why didn’t BN (then 79 seats) and PKR (48 seats) joined forces on the night of May 9? Together, they have 128 parliamentary seats, more than enough to form the federal government. The problem was Najib could not allow Anwar to become the 7th prime minister for obvious reason. But if Anwar cannot be crowned, why should he join BN to begin with?

Clearly, Mahathir and Daim knew about the possibility that Anwar Ibrahim may throw tantrum if his desire to become prime minister soonest possible wasn’t entertained. That was why Mr. Daim warned that it would be foolish for Anwar Ibrahim to be made prime minister immediately. He told Mr. Anwar not to break the promise about the mid-term transition.

Daim also reportedly lectured Anwar – “You all tried how many elections and failed. Whether you like it or not, Mahathir succeeded.” However, armed with 49 parliamentary seats, Anwar has become arrogant and couldn’t accept that PM Mahathir, despite his party winning only 13 seats, continues to call the shot. Anwar told his boys to make “noises” about PKR being the biggest winner.

When PKR was at its weakest point, they cried, whined and bitched about equal partnership. So, they were given the Selangor state.

Now that they have won the most number of seats, they demanded to be given the most ministries. Having ruled the country for 22 years, Mahathir, however, has decisively made the bold decision to reward all the 3 component parties with important ministries – except PKR.

Perhaps the 93-year-old prime minister could smell a rebellion and UMNO DNA in Anwar’s party miles away. He rewarded Mat Sabu of Amanah with Defence Minister. He appointed Muhyiddin of PPBM as Minister of Home Affairs. And he strategically pampered Lim Guan Eng of DAP with the Finance Ministry portfolio. That made Anwar Ibrahim fantastically furious.

It was an insult that a component party of Pakatan Harapan with the most number of parliamentary seats didn’t get any of the important portfolios. Besides requiring Lim Guan Eng’s track record, there was a political reason to appoint him for the prestigious finance minister post. Mahathir wanted to secure DAP’s loyalty in preparation for any eventuality.

As the first Malaysian Chinese in 44 years to hold the powerful position of finance minister, the ethnic Chinese community was exhilarating and extremely grateful. DAP’s strong 42 parliamentary seats suddenly became Mahathir’s fixed-deposit. Together with Amanah’s 11 seats, Mahathir has in his pocket 66 seats against Anwar’s PKR 48 seats.

We had written why Mahathir couldn’t care less about campaigning in Sabah and Sarawak. Sabah-based Warisan party, an ally of Pakatan Harapan, was part of Mahathir’s chess piece which ultimately contributed 8 seats. Sarawak’s former chief minister Taib Mahmud, popularly known as “Pek Moh (白毛 or white-haired uncle)”, was also part of Mahathir’s men.

Taib Mahmud was supposed to switch side in the event Pakatan Harapan couldn’t win substantial seats. But that is water under the bridge now. Why do you think Taib Mahmud met with Mahathir and Daim on May 11? Sorry folks, the 82-year-old Governor of Sarawak was more useful a free man than a prisoner as far as Mahathir’s political manoeuvre is concerned.

Now that the Taib Mahmud’s PBB party had architected the death of BN Sarawak and together with other parties have pledged its support for Mahathir administration, the prime minister’s strength has grown. Sabah (8 seats) and Sarawak (19 seats) are now Mahathir’s fixed-deposit. Altogether, Mahathir commands a strong force of 93 parliamentary seats.

Even if Anwar Ibrahim declares his PKR will quit Pakatan Harapan, not all the 48 MPs will blindly follow him. Only 27 of the 48 PKR MPs are Malays. Now that UMNO is reduced to 54 MPs and assuming Anwar agrees to form a PKR-UMNO-PAS alliance under the pretext of protecting Malays and Islam, their numbers are only 99, still short of 13 seats to form a simple majority.

But even then, not all Malay-Muslims within UMNO or PKR have a death wish of transforming the country into a full-blown Afghanistan. At least UMNO warlord Nazri Aziz has declared that UMNO would rather work with Chinese-DAP than PAS (Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party). Therefore, it’s a wishful thinking that Anwar could become a prime minister in the PKR-UMNO-PAS alliance.

Anwar wanted the powerful finance minister, on top of prime minister, exclusively for himself. This prime minister-in-waiting could be another Najib Razak, if he has it his way. He needs to be controlled and guided. This is another reason why Daim Zainuddin warned that it would be foolish for Anwar Ibrahim to be made prime minister immediately.

It appears that Anwar Ibrahim is another narcissist like Najib Razak. Mahathir’s popularity has hit the roof, and Anwar isn’t impressed. He is trying everything to stay relevant, and get noticed. When Mahathir was trying to get the Agong (King) to accept Tommy Thomas without delay as Attorney General, Anwar rushed to the palace to get the credit.

When the Perak state government tried to get rid of BN appointees from GLCs (government linked companies), Anwar interfered and told the chief minister and excos not to be hasty in taking action on GLCs. Not satisfied with stealing thunder domestically, Anwar flew to London and announced Malaysia will investigate the Battersea Power Station deal.

Still bloody mad after losing the finance ministry post to Lim Guan Eng, Anwar decided to lecture the minister, telling him to be cautious when issuing statements so that foreign rating agencies such as Moody’s will not get offended. Acting like a real prime minister, Anwar said Lim should leave the exposes of misconducts of the previous government to other ministries.

Amusingly Lim Guan Eng told Anwar that his actions of revealing the previous regime’s financial scandals were done on the instruction of Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. Mr. Lim also lectured Anwar that as the person in charge of the Finance Ministry, he was not in a position to instruct other ministers to reveal scandals which happened in his own ministry.

Anwar is trying too hard to boost his popularity that he didn’t realise he looks quite idiotic. You can bet your last penny that when he takes over from Mahathir in 2 years time, Lim Guan Eng would be booted from the finance ministry. Anwar Ibrahim believes he’s the best man for the job. And this is why Daim said it would be foolish for Anwar Ibrahim to be made PM immediately.

Copyright 2006-2018. FinanceTwitter. All rights reserved

June 9 marked one month after the historic GE14. It is early days yet for the new Pakatan Harapan government with only a core minimalist cabinet in place. Yet, in the past month, there have been important messages that illustrate a commitment to a genuinely different form of governance.

At the same time, the cautious and more constrained manner Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad has gone about making important decisions showcases the different style of coalition politics that now operates in an arguably more challenging political environment than that faced by BN in the past.

Despite serious obstacles, Malaysia is embracing a ‘new politics’.

Meeting promises

To date, Harapan can point to four important areas where it has fulfilled its campaign promises.

The first is the zero rating for the GST, reducing the tax burden of ordinary Malaysians. This is the first step needed to remove the tax altogether when Parliament meets in July. This policy change has been carried out with minimal impact on financial markets, thanks in part to higher oil prices and an open recognition of the need for alternative revenue sources.

Second is securing the release and pardon of Harapan de facto leader Anwar Ibrahim. This took place in record time. While one might interpret the speed of the release on the part of authorities as an effort to fuel division and competition within Harapan, this move on the part of Mahathir showed a strong commitment to reform and the partnership within Harapan itself.

Third is the increased transparency of the new government, with many ministers regularly meeting the press and engaging the public and stakeholders. This has indicated greater responsiveness and accountability on the part of the new government from the starting gate. It is especially promising given the inward orientation for fact-finding and learning that is going on.

The greater transparency has revealed some of the problems the government has inherited and can be seen as a needed corrective action to reduce expectations. Key will be whether this pattern of engagement is maintained and how the government offers solutions to the exposed problems.

Fourth are the measures introduced to tackle corruption and abuse of power of the past. From the new attorney-general and police raids to the questioning sessions of a more active MACC, these measures highlight a commitment to dealing with the excesses of the previous government.

Malaysians are awaiting the arrest of Najib Razak and his wife, as revelations post GE14 a.k.a. Pavilion Residences have shown even more abuse to ordinary Malaysians than had been believed before the election. Sadly, more is likely to come as the investigations appear to show that the former prime minister betrayed not only his country but his own party as well.

Making appeals

Harapan has combined these actions by building on four important political narratives.

The first is the continued use of nationalism post-election, as the government has appealed to national pride and reached out directly to citizens. The most obvious example of this is the creation of the Tabung Harapan Malaysia – the crowd-funded initiative to address the public debt. It has reached over RM50 million in less than two weeks. This has tapped into the deep patriotism of Malaysians and has reinforced the view that the government is addressing the serious problems it inherited from the previous government.

A second important narrative is that of inclusiveness. Harapan has repeatedly sent the message that it is a ‘Malaysian’ government. From remarks about a minister’s ethnic identity to the appointments across races, Harapan has aimed for greater representation. This has extended to the inclusion of perceived Islamists within the government in key appointments in education.

There have simultaneously been repeated reassurances that Malay interests will be protected as the aim appears to move the discussion away from division and displacement. Many are awaiting the further 15 cabinet appointments, in particular with regard to East Malaysia, which to date has not adequately been included in the national government, especially given its numerical importance in the composition of the Harapan government.

Building on the anti-corruption measures noted above, Harapan has repeatedly emphasised that it will operate with the rule of law. The perceived lawlessness of the previous government and the arbitrariness of decisions of the past make this a stark difference in governance. It is not easy to change practices and norms, but proper processes and procedures have been given more of a place. The rule of law is now moving away from the practice of using the law to rule.

Perhaps the least touted narrative pre-GE14 is the introduction of greater austerity. Mahathir appears to be introducing more fiscally prudent practices, whether it in salaries or in international trips. This is in keeping with the revelations of serious and significant government debts, but also suggests a more measured approach to governance. There has been less patronage distributed through the use of positions so far.

The message has been sent that the cuts in spending are necessary, not to cover up for lavish spending and scandals such as 1MDB but to address them.

Resistance and resignations

Collectively, these changes in governance speak to a different form of governance. Public expectations remain high and vary sharply, with many of these expectations in contradiction to one another. Choices and priorities are being contested, with some understandably expressing dissatisfaction with the pace of change.

Unlike the BN government, Harapan is operating in an environment where it does not control the mainstream media outlets. It has yet to have a clear media strategy to deliver its messages, opting for less centralisation than the past and more diversity. It has inherited a climate of considerable political polarisation and routinised practices of disinformation.

Harapan also is facing considerable resistance inside, from elites who oppose appointees to more entrenched conservative forces in the system. While it is important to acknowledge considerable goodwill in the public at large, many are suspicious and some are outright hostile and defiant inside the system as they protect their own interests and welfare. Given that this norm of self-interest has been deeply socialised, it is hard to change attitudes overnight.

Many uncooperative senior officials will need to go, with the resignations to date only the tip of what is likely needed. A key challenge will involve winning needed allies and implementing policies, given that the previous government relied on consultants to a greater extent than the civil service. This will require wisdom and balance. The choices of bringing back those with experience in government, such as the former auditor-general, speaks to a recognition of the urgency of gaining control of government inside the government itself.

Some of the resistance is coming from rivalries within the Harapan coalition itself, as the differences over reform, personal positioning and policy priorities have stymied cooperation and slowed decisions. On the whole, these conflicts have been kept out of the public limelight, given the public pressure on Harapan to meet the expectations of its supporters and fulfil the responsibility it has been given.

The realities of Malaysia’s new politics are coalition politics never seen before. This model is based on equality, mutual respect and mutual dependence. This political model will continually need compromise and confidence in each other, not always viable given political histories.

Addressing trust deficits

Building trust is not easy. The trust deficit for the new government is on multiple fronts. It is with the general public socialised in suspicion of government and with half of the population that did not vote for Harapan are watching it carefully. It also extends to the coalition actors themselves within Harapan that are finding their way to work together.

Given the ideological and personality differences within the Harapan government, the outcomes and common narratives so far show that, even with rivalries and uncertainties, the coalition is coming together and a new form of coalition politics is emerging.

Taken from malaysiakini.com

Labels abound to describe what is happening to Malaysian politics since the 9 May 14th General Election (GE14), ranging from “democratic transition” to more ambiguous “change”. Equally varied are the prospects for the country, with scholars touting greater “democracy” and others pessimistically highlighting a return to the worst of the Mahathir Mohamad years, run by a “motley crew” with less-than-favourable assessments of Mahathir and/or Anwar Ibrahim based on views of their pasts.

Labels abound to describe what is happening to Malaysian politics since the 9 May 14th General Election (GE14), ranging from “democratic transition” to more ambiguous “change”. Equally varied are the prospects for the country, with scholars touting greater “democracy” and others pessimistically highlighting a return to the worst of the Mahathir Mohamad years, run by a “motley crew” with less-than-favourable assessments of Mahathir and/or Anwar Ibrahim based on views of their pasts.

The tumultuous political events call out for explanation and analysis. Rather than embedding analyses with superlatives or pejoratives, the focus of this piece is to disaggregate the interrelated developments occurring and to point to the factors that are shaping their outcomes. At this juncture, given the uncertainties surrounding Malaysia’s political future, it is important to lay out the factors and conditions that are shaping political trajectories. It is also important to acknowledge that the scope of issues involved indicate significant political changes ahead.

There are five different important interrelated developments happening in Malaysia.

1. Malaysia’s GE14 Election

The 9 May results calls out for explanation, given the large electoral swings, victory for Pakatan Harapan (PH or Harapan) and devastating defeat for the Barisan Nasional (BN), especially for PM Najib Razak and his party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO).

To date, there are three different frameworks to understand the results.

The first focuses on agency, namely the role of leaders in shaping the outcome. Here attention focuses on the liabilities caused by Najib (and his wife Rosmah Mansor), the “game changer” role of Mahathir and the foundational role of Anwar in shaping the reform movement and opposition.

The second highlights more structural socio-political forces. These include the centrality of nationalism in the election, deterioration of political institutions within the BN, notably UMNO, the expansion of the reform movement through organisations such as Bersih, the reconfiguration of the former political opposition (Harapan) through learning and compromise, the impact of taxation and economic conditions of inequality and precarity, as well as effects of globalisation and contraction of social mobility.

The third frame concentrates on the dynamics in the campaign—the interaction of factors that created the momentum of the “perfect” political storm of 9 May. Here we witnessed the use of emotion, the control of political narratives, viral use of WhatsApp by ordinary citizens, and strategic entry into the campaign of former civil servants, which served to inspire defections of UMNO loyalists and the showcase of the ineffectiveness of the BN’s electoral tactics. Campaign developments also highlight the limits of polling to predict results, and the central role that the behaviour of ordinary citizens had in determining the outcome.

These frameworks speak to how differently Malaysian elections are understood and point to varied assumptions about future trends—whether it involves the behaviour of leaders, socio-political conditions, or public narratives.

As analyses continue, there are likely to be further expansion of these frames and intensive debate on the causes of the electoral outcome(s). Key to this will be more in-depth analysis of the results themselves. My own preliminary analysis shows, for example, considerable erosion of support within the UMNO grassroots (with movement to both Pakatan Harapan and PAS, Malaysia’s Islamic party), as well as the critical role of swings in Sabah and Sarawak in the final outcomes—highlighting the need to look at UMNO and campaign dynamics in East Malaysia. This is likely to be one part of a more complex picture.

2. Malaysia’s Electoral Turnover

The day after the election was arguably one of the most important in the country’s history, when a turnover of government occurred after nearly 61 years. The immediate post-election period is less known, as much of the developments happened behind closed doors.

What is public is that the day-long delay in the swearing in of Dr Mahathir as prime minister, statements and tweets by political actors, changes at the state level of the Sabah government, and subsequent revelations of offers to the premiership to Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail point to resistance inside the system to acceptance of the political mandate of Dr Mahathir. Najib’s unbecoming post-election claim that he “gave” up power, given the realities of his loss and the requirements of the Constitution, suggests that he was considering alternatives.

History will likely reveal more of this critical juncture, but here too we can look at the role of individuals, structures, and interactive processes in understanding this outcome, especially compared to other important political junctures of 1969 and 2008.

Among the individuals that will stand out in 2018 are members of the royalty, leadership of the police and civil service, and members of UMNO—insiders who opted for the turnover. My own view is that economic conditions placed greater constraints on the system, as the impact of further political turmoil and potential violence would have had a decisive impact on Malaysia. Research on critical junctures of power point to the role of pacts and cooperation, and what is striking about Malaysia’s turnover is that the pact has apparently not included Najib as he is to (rightly) face the “rule of law” for his reported abuses of power.

The electoral turnover raises issues that will shape the political path ahead—the importance of the royalty as an arbiter, the potential instability that comes with a small margin of victory in terms of seat numbers (at both the federal and in some states), and the central role that trust inside PH will play in its viability as government.

3. Reconfigured Political Actors

This segue highlights that there is now a new government and opposition. This is not just a matter of changed roles, but significantly different coalitions and relationships from the past.

Harapan may have taken over the mantle of national leadership but it is based on a different formula inside the coalition than BN. Rather than dominance of one party, there is greater equality of the different parties. How much power they will have is likely to be challenged and compromises will have to be made. Complicating this further is the pact that has shaped the future of national PH leadership: that of Mahathir’s promised transfer of leadership to Anwar.

Harapan is primarily comprised of familiar political figures, but in quite different relationships with each other. It is a relatively new coalition (together less than a year), brought together primarily for the shared goal of ousting Najib from power and secondarily to bring about further economic and political reforms. Unlike BN, there is considerable ideological difference inside the coalition, with stark differences over economic and political policies. These differences extend to different views of economic reform, affirmative action, the role of race and religion more broadly, and the scope of political reform. This is compounded by the personal tensions that have been played out publicly in the past and are likely to shape the future. How cohesive and directed Harapan will be is uncertain, but what is certain is that these relationships will be tested (and retested) in the months ahead.

Harapan faces the challenge of building trust inside itself, which is being pressured by trust it has been given by the public at large in the election. There are forces that will work to build on potential divisions, as the conservative resistance to reform in Malaysia coexists with more progressive forces.

We can again see this development tied to individuals—their ability to lead, to compromise, to get along and move forward—and their personal narratives of sacrifice and statesmanship. We can also see these developments tied to political forces and pressures in society that are likely to continue to actualise their power and put pressure on the new government from inside and in the public at large. Lessons show that greater inclusion can mitigate instability but at the same time this inclusion will require patience and hard work to resolve differences. The compromises made at the early stages of government will likely set the parameters of any reforms.

A crucial part of the new political context involves the reconfiguration of the opposition itself. As Harapan faces the pressure to become like the BN, the coalition that Tun Razak formed has died—killed by his son. The parties involved are choosing their exit strategies, seeking relevance in irrelevance for some (such as the MCA and MIC), seeking safety in place (such as many of the BN component parties in East Malaysia) or seeking a new formula for political survival. The death blow for BN in GE14 has come as a shock to many, and the BN component parties are slowly coming to terms with the reality that they are no longer in power, and no longer with the same level of access to power and state coffers.

Choices ahead will likely be contested, as each of the parties will fight over spoils and exit/future strategies. None of them have escaped severe wounds. UMNO in particular has been politically decimated, losing half of its seats—which now number 54, only 24% of the parliament. MCA has one man standing, and even this is being challenged in an election petition—MCA is essentially over as a party, with its sellout to China rather than representation of Chinese Malaysians a crucial part of its death knell.

The only real survivor will be UMNO, but the battle ahead within it will be fierce as there is contestation between “old” and “new” forces—those wanting to focus on race and religion and those wanting to move away from this model. The shadow of being declared illegal is ever-present, as Najib’s mismanagement of the party extended to putting the party’s legal future in jeopardy. UMNO will have a hard time thriving without access to state resources. Scholars are already coming together to analyse UMNO’s future—with a new revised End of UMNO? in the works—but questions of leadership, ideology and the party machinery are already being played out in public. What is clear, however, is that Najib’s leadership of the party—where he made the party his own vehicle and in effect destroyed the connection of the party to responsible national governance—will be a difficult legacy to step away from, especially given the previous acquiescence of current leadership contenders to Najib’s political excesses.

Not to be left out is the prominent role of PAS, now holding onto 18 parliamentary seats and two state governments, one of which (and arguably two) they hold due to the facilitating role of Najib’s cooperation with the party. PAS adopted a two-prong strategy in GE14: to be “open” to UMNO (thus receiving considerable support and benefitting from the erosion from this party) and to embrace an exclusionary conservative religious/racist agenda under the leadership of Ustaz Hadi Awang.

These decisions will have their own reverberations as PAS faces pressure inside its own party, especially over the alliance with UMNO. Few in PAS fully appreciate that the decisions surrounding GE14 cost them a role in the federal government and the chance to genuinely become a national party, as Hadi has relegated its political centre to its traditional base of the East Coast heartland. Perhaps even more significant will be the potential impact the change in government will have on the PAS conservative agenda, as Pakatan is arguably more secular than BN had become under Najib. How PAS moves ahead—in terms of its leadership and alliances, and its mobilisation of conservative forces in Malaysian society—are responses to the GE14 campaign itself and will set the course of the debate.

Both UMNO and PAS have been weakened by GE14, and will likely to be internally focused for some time, but the tactics they adopt ahead set the parameters for political discourse. There are considerably darker forces in Malaysia’s political life that will need to be controlled and dampened. Malaysia needs a strong constructive opposition. The battle is on for whether the new opposition will in fact be destabilising or positive for Malaysia’s future.

4. Reassessing Najibnomics and Economic Reform

Amidst these political machinations are serious demands for reform, as the GE14 has opened up long-contained cauldrons. The new government has prioritised the economy, and this is long in coming. While growth numbers have appeared positive, the fundamentals in the economy have been less favourable—as is evident in the election result against Najib. The need for substantive economic reform has been clear since the 1997 Asian financial crisis and has been exacerbated by Najib’s mismanagement of the government-linked companies and recklessness in handling national debt.

The issues go well beyond the scope of this short piece but worth highlighting given that it is essential to understand that Malaysia is now facing broad changes. Given the close ties between the economy and political life in Malaysia, changes in the economy will inevitable affect the former and vice versa.

Attention has centred on the multi-billion dollar 1MDB debacle, and Malaysia is likely to set an important international example in the implementation of the rule of law with this scandal, as Malaysians count the minute to Najib’s incarceration (as well as the disgraceful number of handbags).

There are three broad areas that are worth drawing attention to as Malaysia moves ahead—a) the future driver(s) of economic growth, b) the introduction of a needs-based social policy to address the class, racial, regional and gender inequalities and problem of contracting social mobility and c) the management of the state sector and its relationships in the political economy. All of these areas are being reassessed as the new government comes on board, highlighting that there are both opportunities and constraints in bringing about economic reform. Not least of these are different international conditions.

There is little consensus on Malaysia’s economic reform trajectory and given the lack of understanding outside of Malaysia of the appreciation for the need for greater transparency, and likely readjustment of the numbers underlying economic conditions (as the Najib administration played loose in the assumptions of its financial projections), this will be a challenging path ahead.

5. Reversal of Democratic Decay

Similar factors shape the debate over political reform. A wide-agenda has been incorporated into the Harapan manifesto, from the role of the prime minister to changes in the electoral commission. There are different priorities, further complicated by the reality that the current prime minister is responsible for deepening democratic decay. Public debate in the wake of the election has showcased the breadth of concerns—from corruption allegations against Taib Mahmud in Sarawak, to the murder of Kevin Morais and trafficking victims in Wang Kelian, as just a few examples—with different positions taken on the role of the police, civil servants and businessmen (or cronies).

Among the long list of political changes are legal reform and justice in cases, changes to political institutions to strengthen checks and balances, institutional integrity, efficiency and governance, reducing corruption, electoral reform, improving race relations and religious administration in areas such as Islamisation, protecting human rights and rebuilding of the education system—and this is not an exhaustive list. There are debates over these areas and over which should take priority, and, significantly, there is resistance to reform both inside and outside of the political system. Studies have shown repeatedly that Malaysians have different visions of democracy and their political future, with many more conservative forces for example seeing Islam as political empowerment. It would be a mistake to assume that the political polarisation of the past is not in the present, as fewer than 50% of Malaysians voted for Harapan.

Beyond different outlooks is the challenge of implementation of reform, given resistance inside the system to change and the decay of the civil service over time, in large part exacerbated by Najib’s deep spending cuts and politicisation of governance. The new government will need to remove Najib loyalists while simultaneously building on the goodwill in the system and making allies with those in the second tier of the bureaucracy.

As Malaysia moves forward, there will be steps back, sideways and delays ahead. Leadership, socio-political conditions and interactive processes will combine to set the direction(s) ahead, which at times will likely appear contradictory and inevitably fail to meet the varied expectations of Malaysians and outsiders alike. The last two weeks, however, are promising and speak to the bold and profound path of change that the country is embarking on. Harapan—hope—has lived up to its name—so far.

Taken from New Mandala. This article is based on the following public lecture given at the Australian National University